Diels-Alder-like reactions

Introduction

The Diels-Alder reaction is a powerful means of building six-membered rings from two simple reactants. The reaction involves the creation of two sigma σ bonds and a pi π bond while installing up to four new stereocenters. The resulting cyclohexene ring is readily transformed into useful structures, and this has seen the Diels-Alder reaction finding extensive use in synthesis.

The previous summary (HERE) covered the basics of the ‘normal’ version of the Diels-Alder reaction in which an electron-rich diene reacts with an electron-deficient dienophile. It gave a simple method to predict both the regioselectivity and the stereoselectivity.

This summary shows how the same principles can deliver a host of different six-membered rings, extending the use of the Diels-Alder reaction.

Background

A typical Diels-Alder reaction is shown below. The electron rich diene reacts with an electron-deficient dienophile to give a cyclohexene. This combination of reactants is sometimes known as a normal Diels-Alder reaction. The regioselectivity, which carbon joins to which carbon, can be predicted by looking at the polarity of the bonds. For the diene, the ether feeds a lone pair of electrons into the conjugated diene. This makes the terminal carbon the most partially negative or δ–, and leaves the carbon at the other end of the diene partially positive δ+. The dienophile is an activated alkene, the nitro group pulls electrons towards it leaving the β carbon partially positive or δ+. The partial charges are matched so that the δ– carbons react with the δ+ carbons. While not strictly true, this method predicts the regiochemical outcome of most Diels-Alder reactions.

A summary of the Diels-Alder reaction. The regioselectivity of the reaction can be predicted by inspecting the polarity of the bonds. The stereochemistry can be predicted by drawing an overlapped transition state that maximizes secondary orbital interactions or favors the endo transition state in which the electron withdrawing group of the dienophile in under the diene.

Diels-Alder reactions are concerted resulting in a stereospecific reaction where the geometry of the initial alkene double bonds is maintained in the relative stereochemistry of the product. The trans alkene of the dienophile leads to an anti relationship between the substituents marked * in the diagram above. Diels-Alder reactions are also stereoselective and the orientation of the two reactants can lead to diastereoisomers. The exo product is favored in the ‘normal’, electronically matched, Diels-Alder reaction due to secondary orbital interactions. The stereochemistry can be predicted by drawing the reactants overlapped and mapping this back to the finished ring. This is a simplification of the transition state, which resembles the boat conformation of cyclohexane.

The key to these reactions, as with so many, is that a nucleophile, an electron rich species, reacts with an electrophile, an electron poor substrate. As long as you match the electronics, then it possible to alter the substrates. You can enhance selectivity by magnifying the electronic differences or altering the steric environment. You can change virtually any atom to allow different six-membered rings to be formed. This summary shows some of the more common variations on the Diels-Alder reaction.

Catalysis

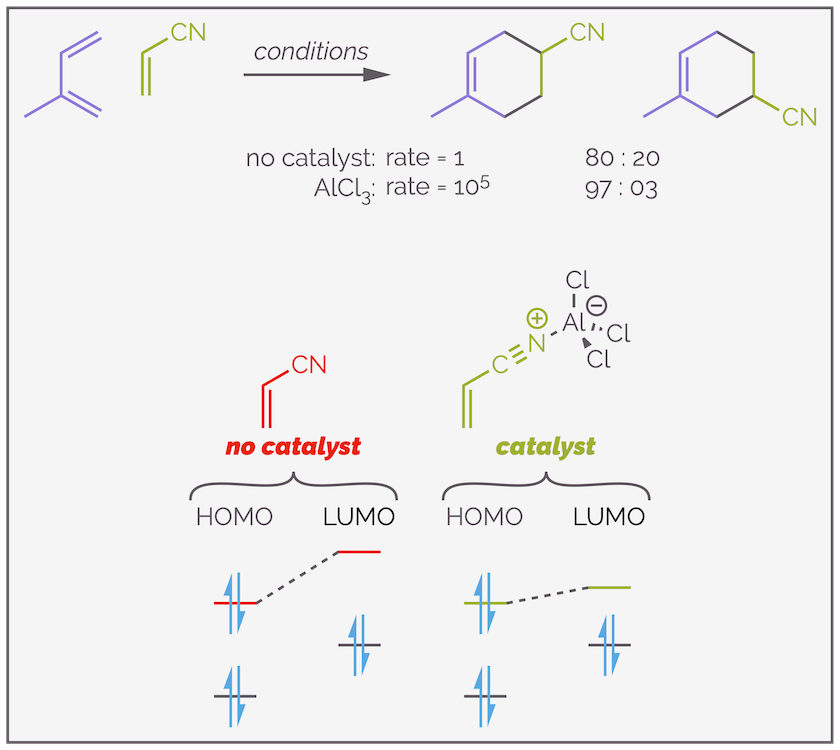

Adding a Lewis acid to a normal Diels-Alder reaction leads to enhanced rates of reaction and increased selectivity, all while presenting an opportunity to perform the reaction at lower temperatures. A Lewis acid is a compound that accepts electrons. By coordinating to the lone pair of electrons on the nitrile it activates the dienophile. The traditional argument for this (meaning some chemists disagree) is that the Lewis acid lowers the energy of lowest occupied molecule orbital (LUMO) of the dienophile. The smaller the energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO, the faster the reaction. The addition of aluminium trichloride leads to the reaction below being 105 times faster than the reaction without Lewis acid.

The effect of a catalyst on the Diels-Alder reaction. Addition of a Lewis acid increases the rate of reaction, allowing reactions to be performed at lower temperatures and with higher selectivity. This version has a 10^5 rate acceleration and the regioselectivity increases for 80% to 97%. The simplest rationale for the acceleration is that the Lewis acid coordinates the dienophile and lowers the LUMO.

You can add a sub-stoichiometric quantity of the Lewis acid (erroneously known as a catalytic quantity ... but such a phrase is meaningless if you think about the definition of a catalyst) as the coordinated dienophile will react faster than the non-coordinated. This means the majority of the reaction proceeds through the coordinated reactant.

As the example above shows, not only is the reaction faster but it is also more regioselective. The Lewis acid accentuates or enhances the difference in orbital coefficients. It makes the electron-withdrawing group more electron deficient and this causes greater polarization of the alkene. The terminal carbon is more partially positive or more δ+. This carbon is more reactive and the reaction is more selective.

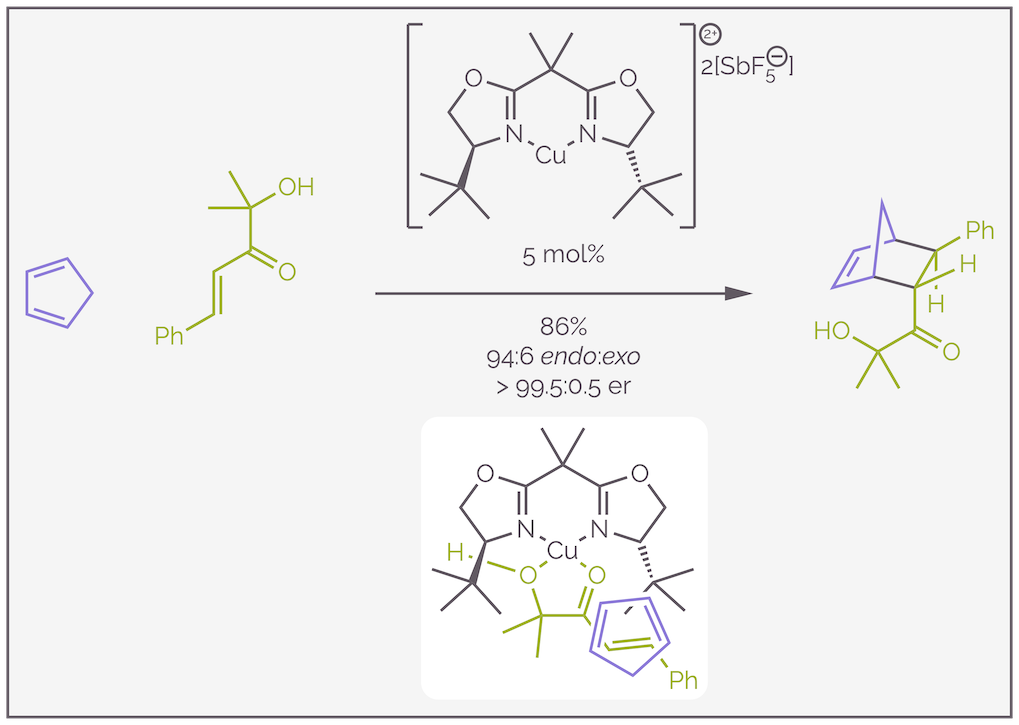

The use of Lewis acid catalysts presents the opportunity to influence stereoselectivity. It is possible to synthesize chiral Lewis acids by adding the appropriate ligand. The Diels-Alder reaction then occurs in the a chiral environment, the catalyst effectively creating a pocket which encourages the reactants to meet in a specific orientation. The reaction preferentially occurs in the presence of the Lewis acid rather than as an uncontrolled background process due to the acceleration discussed above. A classic example of this control is shown below (reference https://doi.org/10.1021/ja0368002). Here a mere 5 mol% or 0.05 equivalents of catalyst accelerates the reaction and controls the selectivity so that less than 1/2% of the wrong enantiomer is formed.

An enantioselective Diels-Alder reaction. The copper(II) Lewis acid is complexed to a bisoxazoline, or BOX, ligand. It coordinates with the α-hydroxy ketone to create a rigid chelate with one tert-butyl group blocking approach of the cyclopentadiene from the bottom, so it approaches from the top. This controls the enantioselectivity. The diastereoselectivity arises from the preference for the endo transition state and stereospecificity of cycloadditions.

An aside:

While an explanation of the stereochemical outcome of this reaction is beyond the scope of this summary (I don’t want to distract from the purpose of the summary), it is interesting and I have given a potential transition state. The reaction requires a bidentate dienophile to ensure that when it coordinates to the Lewis acidic copper(II) complex, it forms a rigid chelate. This means there is little conformation freedom or rotation of the bonds. The copper(II) is assumed to have a distorted square planar geometry, and this allows me to get away with drawing it as the flat cross shown in the diagram. The ligand is a bisoxazoline or BOX ligand. These are readily formed from amino alcohols, themselves derived from amino acids, a cheap source of chirality. This BOX ligand is C2 symmetric (it lacks a mirror plane but does have axis of rotation). It means that it doesn't matter if I draw the alkene on the righthand side (as in the diagram) or the left, the same face of the alkene is blocked by one of the tert-butyl groups. The steric hindrance means the diene must approach from one face (the Re face for those that care about such things). This controls the enantioselectivity. The diastereoselectivity arises through the normal preference for the endo transition state and the stereospecificity of cycloadditions.

Interestingly, the argument that Lewis acid catalysis accelerates the Diels-Alder reaction by lowering the LUMO of the dienophile has been called into question. Both the diene and the dienophile act as the nucleophile and both act as the electrophile (looking at the curly arrow mechanism, each component both donates and accepts electrons), the original idea that lowering the LUMO of just the dienophile aids the reaction is on shaky ground (yet appears in nearly every textbook). This would slow the other bond forming process. It is now believed that the electron withdrawing ability of the catalyst reduces the electrostatic repulsions between the three alkenes involved in the reaction. By reducing the repulsion of the three π systems, the rate of reaction is enhanced.

There is another means to accelerate the Diels-Alder reaction, and this almost certainly does reduce the LUMO of the dienophile. By using a secondary amine as an organocatalyst, it is possible to convert a conjugated enal into a conjugated iminium ion. The positive charge makes the dienophile more electron deficient and accelerates the reaction. Again, if the catalyst is chiral it can induce enantioselectivity in the cyclization. A classic example comes from the research group of David MacMillan, who won a share of the Nobel Prize for his work on organocatalysts (Ref: https://doi.org/10.1021/ja000092s).

An example of the Diels-Alder reaction accelerated by an organocatalyst. The reaction proceeds by the formation of a charged iminium ion that makes the dienophile more electrophilic. The enantioselectivity is due to the phenyl substituent of the catalyst blocking one face, the Re face, of the alkene. The diene must approach from below. The diastereoselectivity if the reaction is poor, it just favors the exo product.

The commonly cited model for the selectivity involves iminium ion formation so that the benzyl substituent of the catalyst and the alkene on the same side of the iminium double bond or cis to each other. It is argued that the gem-dimethyl group causes greater repulsion and that there are attractive π interactions between the alkene and the phenyl ring, although it should be noted that computional modelling does not appear to support this. The phenyl ring blocks approach of the diene from the top, Re face. The diene must approach from below (the Si face). The diastereoselectivity is low suggesting that either there is little secondary orbital interactions or the reaction is reversible. Once the cycloaddition has occurred there is a hydrolysis step and the aldehyde and the catalyst are regenerated.

Few Diels-Alder reactions are performed without a catalyst of some sort. Catalysis allows the reaction to be carried out under milder conditions, quicker and with better selectivity. All this leads to higher yields.

The Intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction (IMDA)

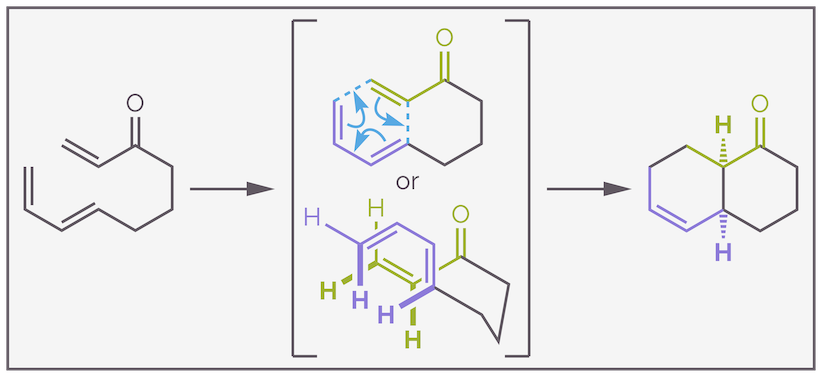

Funnily enough, in an intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction the diene and dienophile are linked together in a single molecule. Upon cyclization, two or more rings are created, the six-membered ring formed by the Diels-Alder reaction and the other ring formed from the linker. Intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions often occur with excellent regioselectivity and diastereoselectivity, with the linker controlling regiochemistry and often restricting the conformational freedom of the molecule. The preference for endo selectivity is not as important as the size of the linker. Below is an example that forms two six-membered rings. It proceeds through an endo transition state but it should be noted that the IMDA displays more variation than the intermolecular Diels-Alder reaction.

An example of an intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction (IMDA). The regiochemistry is controlled by the length of the linker connecting the diene and the dienophile. The transition state shows the curly arrow mechanism and the overlap of diene and dienophile allows prediction of the relative stereochemistry.Make it stand out

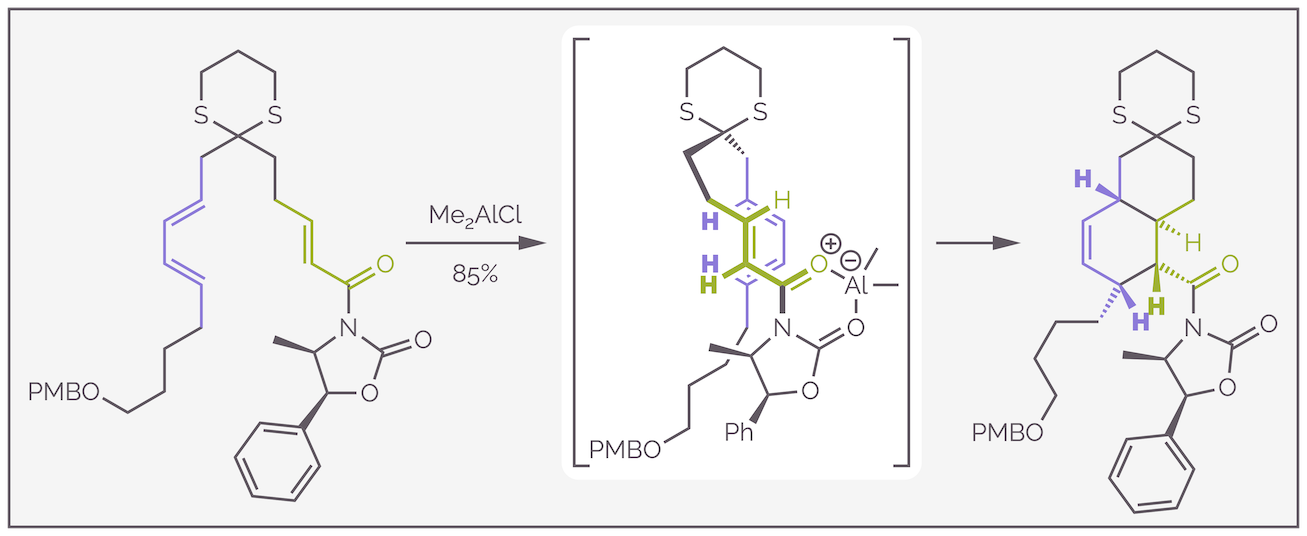

A second example of an IMDA reaction comes from a synthesis of stenine, a molecule found in Chinese herbal medicines (Ref: https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-3765(20011001)7:19<4107::AID-CHEM4107>3.0.CO;2-K). The aluminium reagent serves two roles. It activates the dienophile and it locks the conformation of the chiral auxiliary. The diene favors approach from the bottom face (as drawn below) to avoid interactions with the methyl group of the N-acyloxazolidinone. This explains the absolute stereochemistry of the final product. The diastereoselectivity is a result of the endo transition state. The normal explanation that secondary orbital interactions cause this preference are reinforced by a steric arguments as well. The authors believed that a 1,3-diaxial interaction between the diene and the dithiane (C–S bond) destabilized the exo transition state. I have used the overlapping representation of the transition state to show that three of the hydrogen atoms of the diene and dienophile will end up on the same face of the cyclohexene ring. This beautiful example forms four contiguous stereocenters in a single step. These are used to control the remaining three stereocentres that are found in the final product.

Make it An example of an intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction taken from the synthesis of stenine. The proposed transition state suggests that reaction proceeds through an endo conformation.stand out

This example demonstrates the value of the Diels-Alder reaction. It is a reliable reaction (as reliable any chemistry is) that forms two bonds and multiple stereocenters. It is predictable. It is mild. It’s great.

Hetero-Diels-Alder (hDA) reactions

The Diels-Alder reaction is controlled by the movement of electrons. As long as you have six π electrons in three multiple bonds (two of which are conjugated) then the reaction is possible. The electronics should be matched with one component being electron rich and one electron deficient if you want a good yield. This means the actual atoms are not important and you can swap one, or more, of the carbon atoms with a heteroatom (this means any atom other than carbon or hydrogen but in this case I really mean nitrogen or oxygen) and form a heterocycle.

You can replace the alkene of the dienophile with a nitroso group to prepare a heterocycle as shown in the scheme below. Here the electron deficient acyl nitroso group reacts with a diene to give a bicyclic precursor to the alkaloids (+)-azimine and (+)-carpaine (Ref: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(00)75847-3 & https://doi.org/10.1021/ol030088w). The reaction proceeds through the oxidation of a hydroxamic acid with periodate. This forms the double bond of the acyl nitroso group and initiates the hetero-Diels-Alder reaction. The existing stereocenter influences the formation of two new stereocenters. The diastereoselectivity isn't brilliant but is still useful. A possible explanation (but as stereoselectivity decreases so it becomes harder to predict what is happening) involves a chair-like conformation for the linker, which allows the standard boat-like transition state for the Diels-Alder reaction.

An example of an intramolecular hetero-Diels-Alder reaction taken from the synthesis of two alkaloids. The reaction is initiated by oxidation of a hydroxamic acid to an acyl nitroso compound. The electron deficient nitroso group acts as a dienophile. An existing stereocenter influences the conformation of the molecule and this biases the diastereoselectivity.

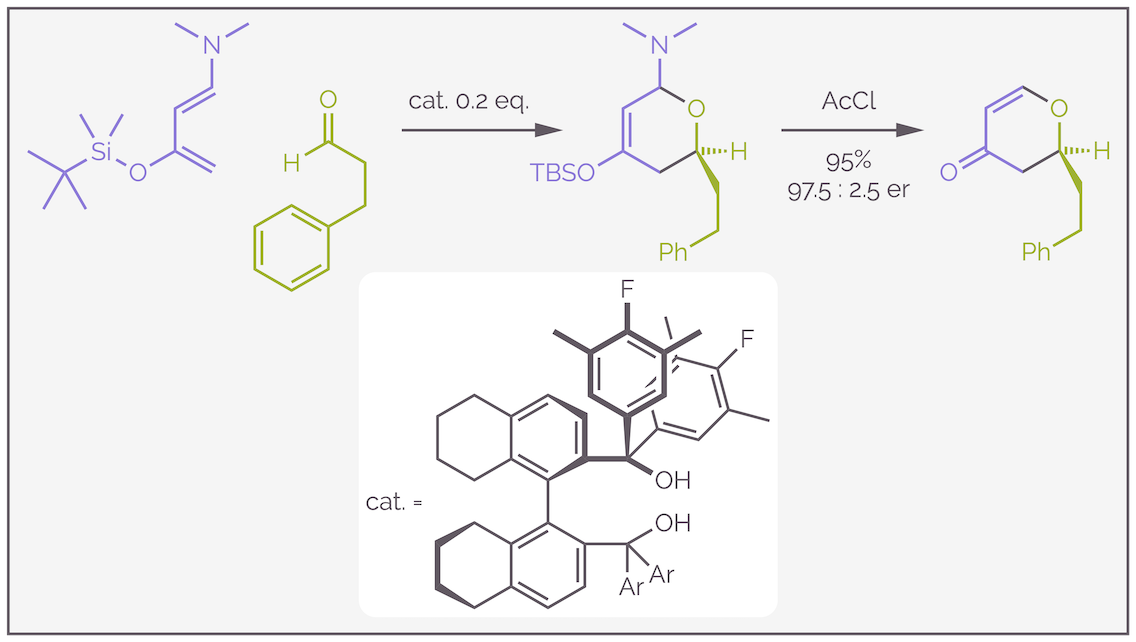

Another example of a hetero-Diels-Alder reaction has an highly electron rich diene attacking an aldehyde to give, after acidic work-up, a dihydropyranone. The example below combines the hetero-Diels-Alder reaction with chiral catalysis in the form of a diol. The diol acts as a hydrogen bond donor or effectively a Lewis acid that simultaneously activates the aldehyde and controls the enantioselectivity.

An example of a hetero-Diels-Alder reaction forming dihydropyranones. The diol catalyst activates the aldehyde by hydrogen bonding, this is effectively Lewis acid activation, with the aldehyde being more electron deficient. The electron rich diene attacks and gives the six-membered ring.Make it stand out

Inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction (DAinv)

All the examples so far have involved an electron rich diene and an electron deficient dienophile but there is nothing preventing you from swapping the electronics of the Diels-Alder reaction. As long as the polarities are still match the diene can be electron poor and the dienophile electron rich. This is basis of inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction (IEDDA or DAinv). Usually (but not always), these reaction are also examples of hetero-Diels-Alder reaction and lead to the formation of heterocycles. Remember, reactions are favored when there is a small difference in energy between the HOMO and LUMO (they are closer in energy). This is achieved by adding a electron donating group to the nucleophile to raise the HOMO and an electron withdrawing group to the electrophile to lower the LUMO.

This diagram tries to show how changing the electronics of the Diels-Alder reaction can make the reaction more favorable. In the middle is a the reaction of buta-1,2-diene and ethene. This is not a favorable reaction as the HOMO and LUMO are far apart. On the left, there is a representation of the normal demand Diels-Alder reaction. This has an electron donating group on the diene. This raises the HOMO. There is also an electron withdrawing group on the dienophile. This lowers the LUMO. ΔE, the difference in energy between the HOMO and LUMO is small. The reaction is favored. In an inverse demand Diels-Alder reaction the opposite occurs. The LUMO of the diene is lowered by adding electron withdrawing groups to it. The HOMO of the dienophile is raised by adding an electron donating group. The HOMO and LUMO are close in energy and the reaction is fast.

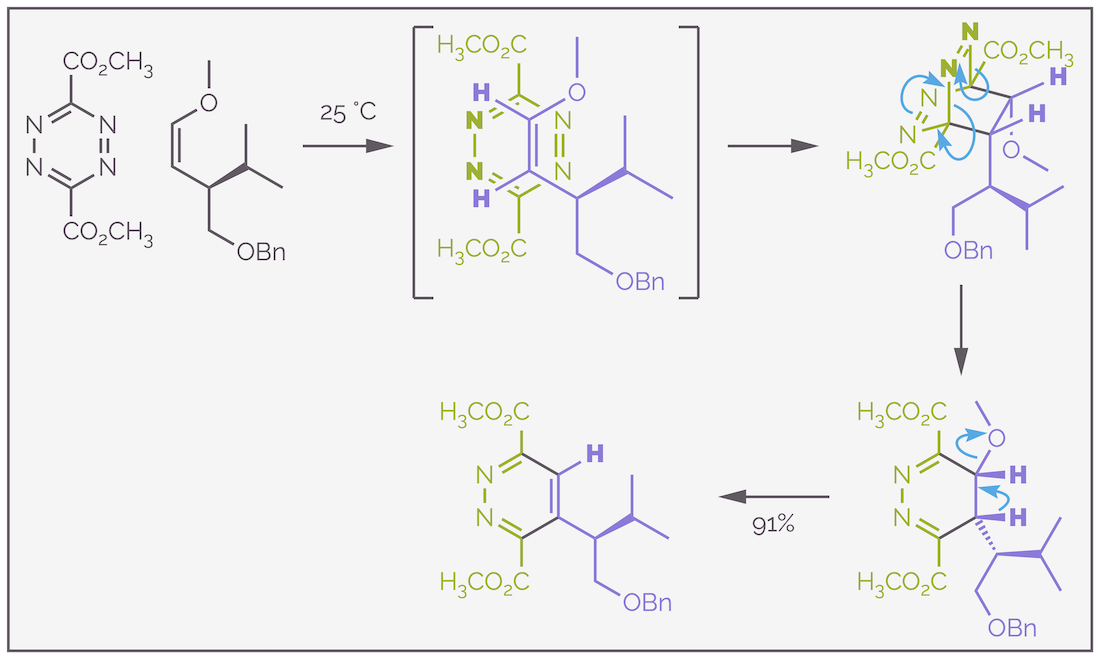

A typical example of an inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction is highlighted in the scheme below, which is taken from a synthesis of roseophilin (Ref: https://doi.org/10.1021/ja011271s). The reaction involves an electron deficient tetrazine, a six-membered ring that contains four nitrogen atoms, reacting with an electron rich enol ether at room temperature. Initially, the reaction leads to a bridged system. I have assumed that the tetrazine approaches the enol ether anti to the bulky isopropyl group. This would be the most stable conformation of the enol ether but the stereochemistry is unimportant as there is only a single stereocenter at the end of the reaction. The bridged ring system breaks apart in a retro-Diels-Alder reaction, an elimination that involves the evolution of nitrogen gas. There is also an elimination of methanol to allow re-aromatization, driven by the stabilization caused by formation of an aromatic ring.

An example of an inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction. First the electron rich enol ether and the electron deficient diene, the tetrazine participate in the Diels-Alder reaction. This gives a bridged species that undergoes a retro-Diels-Alder reaction that eliminates nitrogen gas. The curly arrows are similar to the Diels-Alder reaction. There are are three moving in a circle. Two σ bonds are broken and thee π bonds created. The resulting diene eliminates methanol to re-aromatize. Elimination probably occurs with methanol leaving to give a carbocation. Elimination of a proton gives an aromatic ring.

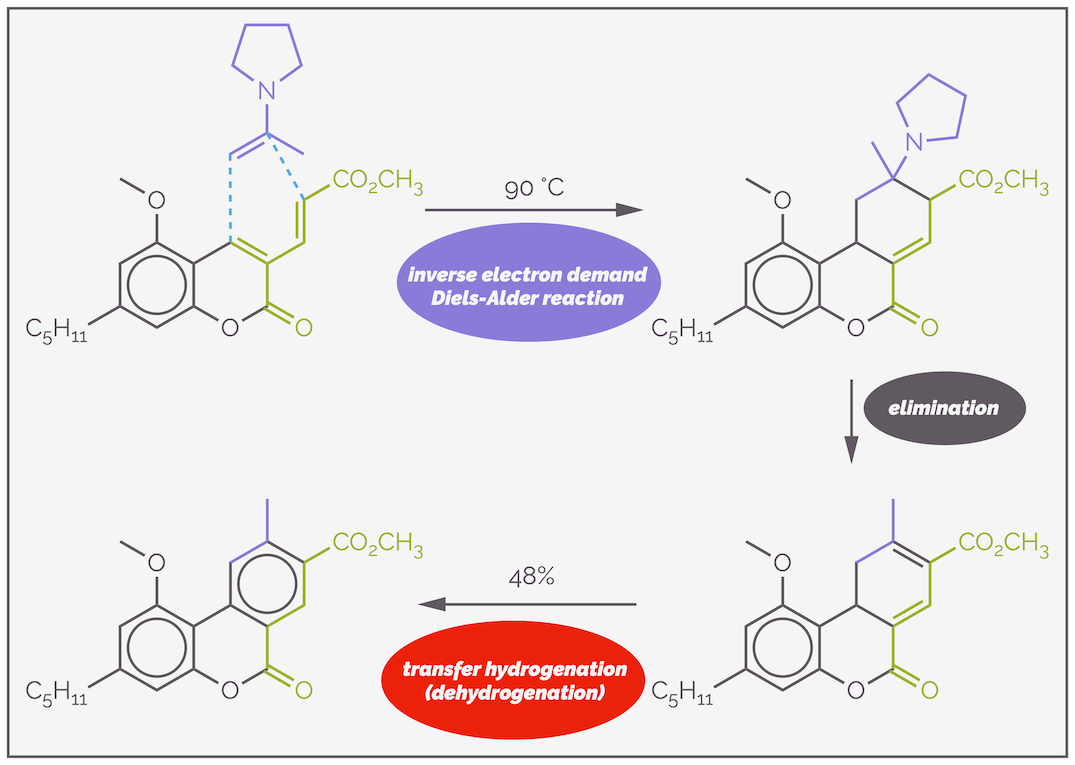

An example of an inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction leading to the formation of a benzene ring is given below and is taken from the synthesis of the cannibinol skeleton (Ref: https://doi.org/10.1021/ol2030636). The reaction involves the addition of the electron rich enamine to an electron deficient diene. Presumably, a cyclohexene ring is formed first. Elimination of the pyrrolidine gives a diene. The latter species is prone to re-aromatization by dehydrogenation. The latter step might involve the transfer hydrogenation of the enamine.

An example of an inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction for the synthesis of a substituted benzene ring. The reaction involves the addition of an electron rich dienophile in the form of an enamine to an electron deficient diene. It is electron deficient due to conjugation to two carbonyl groups. The resulting cyclohexene ring readily undergoes elimination to give a cyclohexadiene. The proton α to the methyl ester is acidic due to the carbonyl and as it is allylic. The elimination is probably E1cB. There is then a dehydrogenation to give the aromatic ring. Cyclohexadienes are good hydrogen sources for transfer hydrogenation, with the driving force being aromatization. Here the diene probably reduces the enamine.

Conclusion

The first introduction to the Diels-Alder reaction presented the basics of this versatile reaction, and how it could be used to synthesize cyclohexenes with up to four contiguous stereocenters. In this summary, the same basic components, a diene, or equivalent molecule with two conjugated π bonds, and a dienophile with a single π bond can be used to form two new σ bonds and one π bond while providing a variety of six-membered rings.

It is possible to enhance the rate of a Diels-Alder reaction while simultaneously improving selectivity by using a catalyst. Most catalysts activate the dienophile by making it more electron-deficient by acting as a Lewis acid or through the formation of an iminium ion.

If the diene and dienophile are linked together the cycloaddition is called an intramolecular Diels-Alder (IMDA) reaction. Such reactions form multiple rings in a single step. Hetero-Diels-Alder (hDA) reactions replace one or more of the carbon atoms of the π system of a Diels-Alder reaction (diene or dienophile) with a heteroatom. This allows you to synthesize heterocycles. Finally, inverse electron demand Diels-Alder (IEDDA) reaction reverses the normal electronics of the reaction with the diene being electron deficient and the dienophile being electron rich. The reaction is still matched, there is a nucleophile and electrophile, and the reaction can proceed under conditions.

It is possible to combine any of these variants to make useful reactions, for example, you can have a catalyzed intramolecular hetero-Diels-Alder reaction.

There is still more detail about these reactions that is useful to learn, especially in terms of molecular orbitals, but what i have covered so far should be sufficient for more undergraduates and the next summary will be on other cycloaddition reactions.